Over the past months, however, Rose’s waves are getting bigger, thanks to the publication of two provocative books and the fortuitous timing of one of them. Two books are Ugly as Sin , an examination of contemporary Catholic church architecture and Goodbye! Good Men, a purported expose of the shortcomings of Catholic seminary recruitment and formation. Both books have received due notice, but the latter, in particular, has attracted a great deal of attention over the past months, as the media and the general public have scrambled to try to understand the roots of the sexual abuse scandal currently rocking the Church. Rose, who holds degrees in architecture and fine arts, wrote an earlier book called The Renovation Manipulation in which he argued that in the years since the Second Vatican Council, many renovation programs of traditionally-designed Catholic churches have been forced upon the laity by deceptive and imperious church leaders and liturgists. Despite what its title might indicate, Ugly as Sin takes a more positive approach to the same problem. Rose first leads the reader through what he terms the “three natural laws of church architecture:” that authentic Catholic church architecture should express verticality, permanence, and iconography, and explains these qualities in terms their expression in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. He elaborates on these three fundamental qualities by taking us, through the eyes of an imaginary “pilgrim” through churches in which these “natural laws” are embodied.

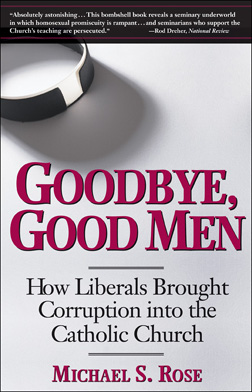

The following chapter then takes a journey through contemporary There is hope, however, as Rose points out in the final chapters of his book. He offers the reader helpful suggestions of how to participate in turning the tide of ugly and secularized church architecture, including a list of like-minded architects and designers. Ugly as Sin is a useful book for anyone involved with the renovation or construction of Catholic churches, a valuable antidote to the “experts” whose advice has done so damage to the structures in which Catholics gather to worship God. Far more incendiary is Rose’s most recent book, Good-bye! Good Men, subtitled, “How Catholic Seminaries Turned Away Two Generations of Vocations From the Priesthood.” Rose’s thesis is that over the past thirty years, many seminaries, diocesan vocations offices and religious orders have come to be dominated by people with heterodox beliefs and sympathy with and even overt participation in various immoral lifestyles, particularly homosexual activity. The result, Rose maintains, is an atmosphere in many seminaries and religious houses in which a heterosexual man of orthodox Catholic beliefs would feel, at the very least, uncomfortable and out of place. At worst, it’s created an environment in which potential seminarians who don’t buy the heterodox agenda (doctrinal liberalism, ethical relativism), practice traditional Catholic devotions and piety, or are uninterested in what Rose calls a “gay subculture” thriving at some seminaries, are rejected as candidates for the priesthood on the grounds that they are “rigid” or “dogmatic” or not “collaborative” enough. Rose backs up his thesis with data culled from the public record – newspaper accounts of seminary faculty and textbook controversies, and even court cases involving accusations of sexual harassment at seminaries. He also uses many personal anecdotes and interviews from men who have either been turned away from priesthood or persisted through great obstacles to ordination. Typical of the cases Rose cites is that of Father William H. Hinds, who was ordained for the Diocese of Covington, Kentucky in 1987. Hinds maintains that because of his orthodox views, particularly on sexual morality, he was singled out by a particular seminary professor who insisted on his meeting additional requirements – independent studies, extra psychological testing – to discourage him from pursuing ordination, despite his excellent academic record and positive reviews from the staff of the parish in which he interned. Goodbye Good Men is a book, that all Catholics concerned about the present and future state of the priesthood should read. You’ll probably be shocked, for Rose holds nothing back, including uncomfortable details and the names of seminaries in which he says Catholic doctrine takes a back seat to contemporary academic fads and, for example, seminarians were transported, with interested faculty, to gay bars on the weekends. There is, however a notable weakness in Goodbye! Good Men that should prompt the reader bring a healthy dose of skepticism to Rose’s claims, implied in the book’s title, that he’s offering an analysis of the complete picture of seminary education in the United States. Goodbye! Good Men may contain lots of stories, and most of those stories may be true, but the fact is, this book is not a comprehensive look at all seminary education in the United States and shouldn’t be read as such. In order to really prove his thesis that there has a been a church-wide conspiracy against the orthodox and the straight, Rose would have to get data from many dioceses, seminaries and religious orders about how many candidates have applied, how many of those have been turned away, and what the reasons for dismissal were. He might even have had to personally visit some of the seminaries which he critiques and do on-site reporting, rather that relying on the testimony of only the dissatisfied. As it is, all we have in Goodbye! Good Men is the story of what happened to a self-selected group of men who attended particular seminaries. It’s their stories, more often than not anonymously related. It’s their side of their stories. Michael Rose is doing important and courageous work, revealing truths that many would rather keep in the dark. But it’s important to remember before being caught up in the sweep of salacious detail and wholesale condemnation of an entire system in Goodbye! Good Men that even though the stories he tells are valuable and important to hear, they're not, by any means, the whole story. |

Catholic churches where, not surprisingly, one finds these qualities ignored, giving the pilgrim a totally different, barely spiritual experience, one that, Rose maintains, has been deliberately evoked by architects and liturgical design consultants who have designed Catholic churches in ways that any inherent sacredness of the space is rejected in favor of values like flexibility and a focus on the assembly.

Catholic churches where, not surprisingly, one finds these qualities ignored, giving the pilgrim a totally different, barely spiritual experience, one that, Rose maintains, has been deliberately evoked by architects and liturgical design consultants who have designed Catholic churches in ways that any inherent sacredness of the space is rejected in favor of values like flexibility and a focus on the assembly.